I have travelled to this temple of glass and granite to read a book that was not meant for me, about things I will never see.

The temperature is just below freezing in Ottawa, and the January sky is clouded, presenting a grey backdrop to the grand atrium of the National Gallery of Canada. A giant spider presides over the entrance. Its eight bronze-cast legs tower thirty feet in the cold air, supporting a steely abdomen and thorax at their centre. Later, I will learn that the arachnid’s name is Maman—mother, in French—and she is a symbol of nurture and protection, carrying her marble eggs and weaving them a silken home. Now, however, her looming presence appears more disconcerting than sheltering. I scurry past her unnoticed. I have not come for her.

The gallery is nearly empty on a Tuesday winter morning. I pass through its clear-vaulted colonnade and Great Hall, where majestic floor-to-ceiling windows look out over the icy Ottawa river and across to Parliament Hill’s gothic architecture. I peek into courtyards and climb up cavernous staircases, until I find a sign directing me to my object. “Nick Sikkuark: Humour and Horror,” it announces. Nick Sikkuark is the author of The Book of Things You Will Never See.

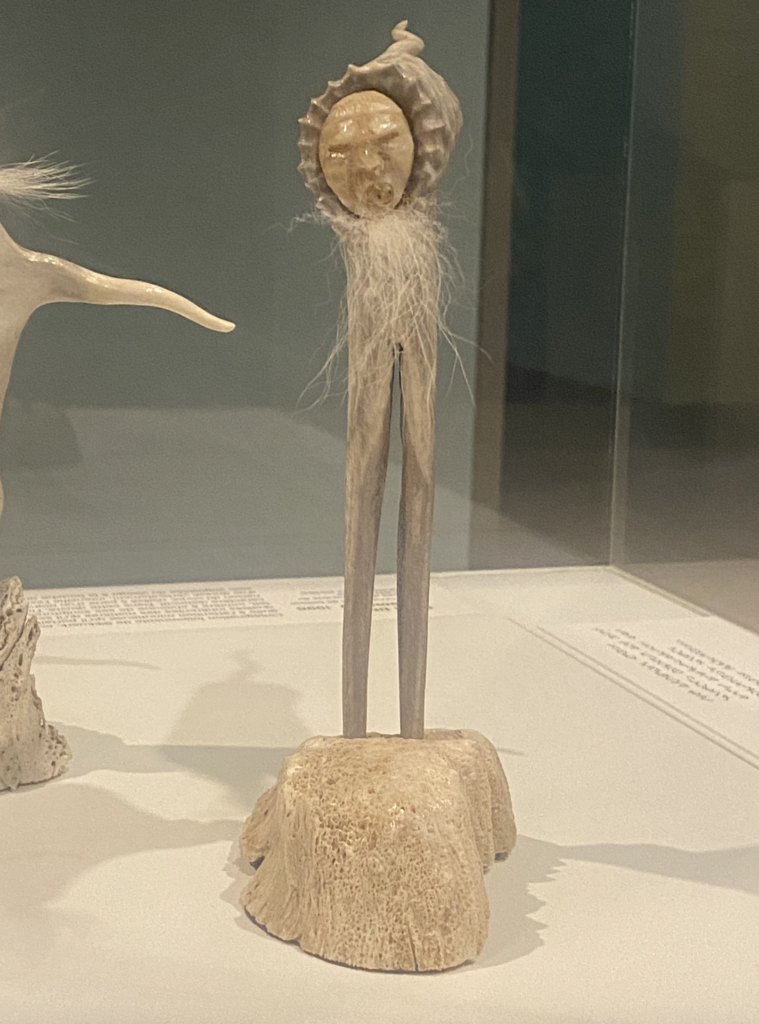

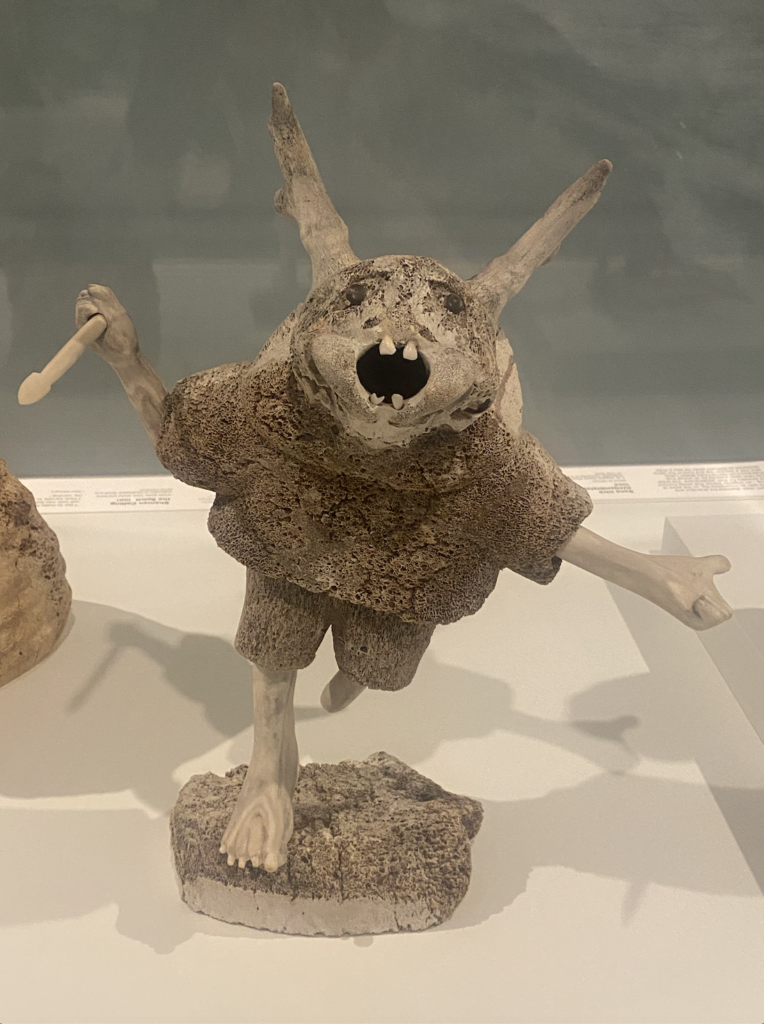

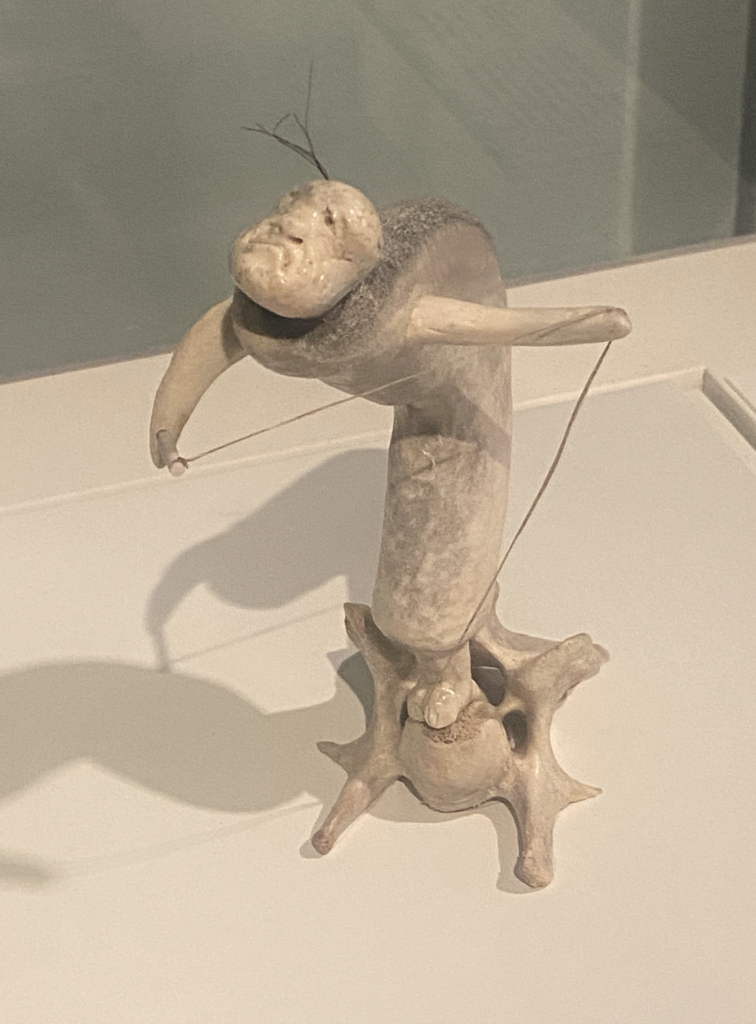

Born in 1943, in what is today the Kitikmeot region of Nunavut—the largest and most northerly territory of Canada—Nick Sikkuark was a self-taught Inuit (Eastern Eskimo) artist with an outlandish imagination. Drawing from his intimate knowledge of the Arctic landscape, he would blend elements of the ordinary and the bizarre in his sculptures and drawings. Known for his macabre wit, he could surprise, even confront, his audience by eliciting mixed reactions of aversion and laughter, twinned catalysts to curiosity. “When I make a carving or drawing,” he pronounced, “I want people to think, ‘What is that? What does it mean?’” Even his children knew, when he sat down to draw, not to ask him to explain what he was depicting—he’d never tell. Instead, they would watch attentively, pulled into his work by their questions and its provocations. Like the rest of his audience, they became co-creators of a story each work seemed to gesture to, in medias res—a story each piece suggested but never quite revealed. As their father would say, “Without a story, there is no art.”

In the early 1970s, Nick Sikkuark was commissioned by the Department of Education of the Northwest Territories—before Nunavut was created—to write and illustrate five children’s books in Inuktut. They were to be “part of a program to revive the use of Indigenous languages by integrating them into school curriculum.” This program was necessary, because Indigenous languages were, and still are, endangered in Canada, as they are around the world. In Canada, this is the result of an array of colonial practices, most notoriously the administration of residential schools—a system of institutions set up by the federal government and administered largely by churches, ostensibly designed to educate Indigenous children and integrate them into mainstream Canadian society. In reality, they amounted to a tool of cultural devastation that forcibly removed children from their families and propagated physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. Children were not permitted to speak their own languages in these schools and were punished for doing so. Since language is perhaps the prime agent through which cultural tradition survives—particularly in oral story-telling cultures—this prohibition endangered not only languages, but peoples, and the cultures in and through which they live.

During the 1960s and 1970s, some began to re-think this approach to Indigenous ‘education’ (though the Residential School System officially remained operative in Canada until the last one closed as late as 1996). Sikkuark’s books reflect this shift.

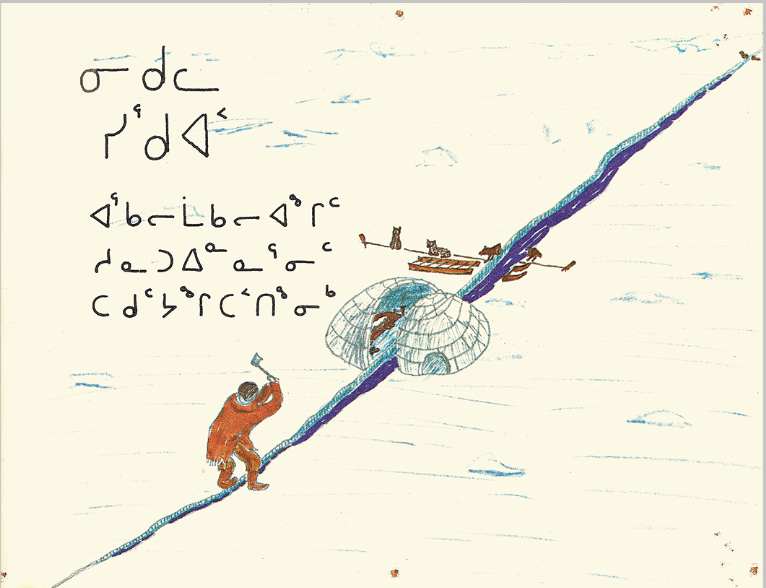

The first of these books is entitled The Book of Things You Will Never See. The cover art of this book (below) gives a good sense of its style and tone.

The Inuktut text reads simply “Nick Sikkuark’s Book of Things You Will Never See.” The image depicts an Inuk, dressed in clothing and using tools—including his axe, Igloo, sled, and dog team—that would be familiar to its intended Inuit audience. Nevertheless, it is a humorously fantastical scene, wherein it appears that the man has chopped the sea ice in two, impossibly also splitting both his igloo and dog sled. The dogs casually look on, lending the scene additional whimsy.

The rest of the book offers similarly strange combinations of familiar elements of everyday life blended with near-nonsensical flights of fancy.

For travellers and readers, like myself, who are not Inuit, such image-text configurations confront us with the challenge of reading these subtle intersections of the familiar and the strange across a cultural divide. They also, however, invite us to interpret that which might be universally human about them. According to the exhibit curator, Christine Lalonde: “Nick Sikkuark: Humour and Horror brings together works that are expressions of individual imagination, deep cultural significance and a generous understanding of our shared human condition.” How do these planes of individuality, culture, and humanity align?

In this image, for example, it is very difficult for me to know precisely what sort of humour is operating. At first, I laughed out loud at this page (disturbing an idle security guard). It takes delightfully surprising comedic turns, first confronting the reader with what seems to be a fantastical beast, only to explain away the fantasy with the rational explanation that this is a mere human being in a costume—provoking us to feel silly for our initial interpretation. But then, the narrative turns on the reader once more, suggesting the costume is seriously intended to help the wearer learn to fly—or perhaps simply express his desire to do so. We cannot be certain if this last proposition should be understood as possible within the narrative. We are caught between modes of fantasy and reality.

Upon further exploring the exhibit, I also came to realize that we might here be presented with a serious and important trope of Inuit oral storytelling: the transformation of shamans into spirits, often appearing in beastly forms. Is this a shaman truly learning to fly? Is he transitioning into a spirit capable of flight?

Later in his career, Sikkuark would mingle the spiritual and shamanic with the natural and human, pulling from the oral storytelling traditions of his culture. It is difficult always to know whether Sikkuark considered these mergers fantastical, or whether they were aspects of reality according to an Indigenous cosmology to which he subscribed. (If the latter, how would this cosmology interface with Sikkuark’s self-declared Catholic faith?). Either way, Sikkuark’s unique combination of fantasy and everyday reality, as Lalonde expertly expresses it, “shows us the natural world inhabited with indwelling spiritual power and connected to all living things.” In other words, it reveals a world to us.

The Book of Things You Will Never See would not qualify as world literature according to most definitions. At least, it is very unlikely to ever appear on a syllabus for a World Literature course. For one thing, it is no longer in print. For another, it is children’s literature, which rarely makes it into any world literature canon. Some might not consider it literature at all, since it was commissioned with a practical, pedagogical purpose in mind—to teach Inuit children to read and write in their own language. I have yet to see any school primers listed as world literature.

And yet, The Book of Things You Will Never See offers readers the opportunity to experience and grapple with the interpretive challenges and delights of reading the world. Even as it announces that it depicts things its readers will never, and can never, see in the real world, it invites a profound engagement with worldly reality.

Not everyone will respond to this invitation in the same way. I am not the intended audience of this book; I can’t even read it in its original language but must rely on translation. I will not, therefore, read the world through The Book of Things You Will Never See as an Inuit school child would. But what this fact reveals is that reading the world through literature is not an individual or isolated act. Just as Sikkuark intended, it is an ongoing practice of co-creation, of joining in a process of storytelling that exceeds our full comprehension. Without such a story, there is no world.

Nick Sikkuark died in 2013 and is buried in Kugaaruk, Nunavut, in accordance with Inuit custom, above ground “looking out on the land that nurtured and inspired him.” This lasting attachment to his home, however, should not obscure the fact that he was also a well-travelled man. He was invited as a contingent of artists to the 1976 Montreal Olympics and attended, as a guest of honour, the 1978 Edmonton Commonwealth Games for which he crafted the official relay baton that carried a message across the commonwealth of nations from Queen Elizabeth II. His connection to these international events highlights that worldliness emerges not only from cosmopolitan centres or global cities. In this case, it comes from Kugaaruk—a place that has been classified, just in the artist’s lifetime, as part of two different territories of the earth’s Far North, despite never having moved.

The worldliness of The Book of Things You Will Never See, however, has intermediaries. I did not travel to Kugaaruk to read it, nor might I ever have learned of its existence had it not been for its inclusion in a curated exhibit in a national art gallery located in a tourism hub. As much as worldliness may seem to exceed nationalism, it is often expressed through the nation and its concrete, emplaced institutions.

This is so because, in effect, the world is a thing you will never see. The world—as a whole world—can’t be seen, nor heard, nor touched. It can only be read through its fragments and piecemeal passages, with much frequently lost in translation.

I make my way back out of the hushed National Gallery, itself now architecturally reminiscent of the Arctic landscapes I have just witnessed—built of amorphous structures as well as crystalline rock. I bid adieu to Maman, whose tenderness no longer seems quite so at odds with her fearsomeness, and I feel how expansive can be the paired experience of delight and disquiet in the face of what we don’t understand. As a soft snow begins to fall, I contemplate how books allow us to travel well beyond geographic limits, making possible experiences of things that we will never see in the real world, but which nevertheless help shape, enrich, and possibly restore it.